See Beyond the Veil

As a life long seeker myself, open to both Eastern and Western religious ideas, I consider this book a portal to enlightenment. Bohlert leads the reader up a spiral staircase to the light, winding through the Christian and Hindu faiths as we ascend. — Nori Muster

This book comes as a cooling breeze on a hot day. It offers a glimpse into an eternal world of love that actually surrounds us at all times. The perfect world that Plato detected, just beyond the veil, really does exist, yet we spin our webs of karma so tightly that we cease to acknowledge it. As you read this book, you hear the music of the spheres, like the rising choral, Ode to Joy, in Beethoven’s final symphony.

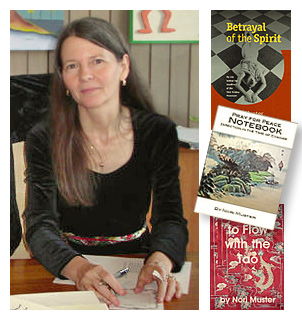

Universalist Radha-Krishnaism — A Spirituality of Liberty, Truth, and Love by Steve Bohlert reviewed by Nori Muster. Nori Muster, a positive thinking modern author of many life engaging books, essays and poetry. Her Betrayal of the Spirit: My Life behind the Headlines of the Hare Krishna Movement, was accepted among many ex Hare Krishna devotees worldwide as a mind-opening narrative and has helped thousands of individuals regain their individuality, sobriety and strength. Learning to Flow with the Tao is Nori’s own version of the ancient Taoist oracle, iChing. Pray for Peace Notebook: Direction in the Time of Change is an edited collection of Nori’s political writings, 2000 to 2009. Visit her website to read more and explore Nori’s wonderful world of positive possibilities.

Author Steve Bohlert dedicated his life to finding the source of the music, which led him to India, where he served and studied with enlightened masters; and it took him to San Francisco Theological Seminary, where he earned a Master of Divinity from the Graduate Theological Union, and became an ordained pastor in the United Church of Christ. He was raised in the Missouri Synod, christened and confirmed.

Bohlert’s life is a bridge between East and West, and a merging of his Christian Universalist beliefs with his strongly held bond with the eternal divinities Radha and Krishna. Universalist Radha-Krishnaism is a product of his studies, and outward manifestation of the bridge he first built within.

The time is right for a book such as Universalist Radha-Krishnaism. As Bohlert points out, “We live in a relativistic, pluralistic world open to truth in all forms.†(p. 5) There is no one way to hold faith, and many in our culture today are searching for truth. As a life long seeker myself, open to both Eastern and Western religious ideas, I consider this book a portal to enlightenment. Bohlert leads the reader up a spiral staircase to the light, winding through the Christian and Hindu faiths as we ascend.

Many of the concepts were already familiar to me, coming from Missouri Synod Lutheran roots, and having spent ten years in the Hare Krishna movement (ISKCON). The Lutherans started out as reformers five hundreds years ago but became quite strict, and as Bohlert points out (p. 5), “most Radha-Krishna devotees are fundamentalist literalists.†It is ironic, but typical, since religious institutions tend to become entrenched in their belief systems, and closed down to change.

Hundreds of years ago, Radha-Krishna, the archetypal goddess and god of love, were little-known outside of India, and worshiped only within the Hindu faith. Eighteenth and nineteenth century archaeologists and scholars made us aware of Hindu gods, but prior to the twentieth century, nobody in the West had any actual experience of Radha and Krishna. Even today, god and goddess remain concealed behind a brick wall of fundamentalism, which most of us from a Judeo-Christian background are powerless to navigate. On one hand, we may sense truth there, but until Bohlert’s interpretation, there was no way to pierce the fundamentalist views and practices that keep these deities off limits. Even the Hare Krishna movement and similar groups may fail to offer a satisfying genuine experience.

One of the subjects Bohlert introduces, which is forbidden in the fundamentalist world of the Hindu sects, including ISKCON, is permission to meditate on Radha-Krishna’s eternal pastimes. ISKCON warns its followers that they will always remain neophytes who dare not dream of life in the eternal realm. This was tried in ISKCON in the mid-1970s, but the fifty or so members of the “Gopi-bhava Club,†as it was called, were scorned and drummed out as heretics. “Gopi†is the Sanskrit word for the cowgirls of Krishna’s world, and “bhava†means “mood, feelings, or emotional state,†so gopi-bhava is the mood of the gopis.

Toward the end of the book, Bohlert offers an outline of a typical day in Krishna’s world with the gopis and other eternal associates, and invites us to imagine how we might fit in. He said Krishna comes around a couple times a day to visit with you, find out how you’re doing, and discuss whatever is on your mind. Since reading the book a few days ago, I have imagined many things I would like to say to Krishna.

Bohlert was a member of ISKCON in the early days of the movement, 1967-1974, when he was starting temples around the world for the founding guru, Srila Prabhupada. Later, he served a one year stint in New Vrindaban (West Virginia), 1980-1981. However, like many of us, he had to leave the confines of the organization to continue his spiritual journey.

In Universalist Radha-Krishnaism, Bohlert speaks without the constraints of fundamentalism, re-imaging Radha-Krishna for the modern seeker. He cites the “evolution of thought†(p. 28) and the need to reinterpret religion in each new generation. Through his long education and practice, he learned that he can be part of the process of religious reform. This book is his way of moving the conversation forward, mingling two divergent religious traditions, and making the supreme Hindu god and goddess accessible to his readers. He dubs Radha-Krishna “God-dess,†which means god and goddess together.

Bohlert dismantles the fundamentalist notion that we come from original sin, that we were put in this material world as a punishment, that our flesh is evil, and that god is a menacing figure who sits in judgment. These fears played a part in the development of both Christian and Hindu theology, and may have helped to enforce discipline on people who lived in previous centuries. However, Bohlert argues in favor of universal love and freedom, which are common tenants of most new age religions. He writes that, “Like any good parents, Radha-Krishna want us to enjoy ourselves. This adds to their enjoyment.†(p. 25) He explains that worldly fun and spiritual devotion co-exist when we learn to live in harmony with god and goddess, nature, and all beings.

Besides citing references from his teachers in India and Berkeley, Bohlert’s opus draws on Plato, Martin Luther, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Carl Jung, the humanists, Jack Kerouac, and quantum physics. He shows how the truth runs through all these rivulets, from Plato’s Theory of Forms, to Carl Jung’s archetypal reality, and ties it all together in his vision of God-dess. He says, “We exist as parts or emanations of God-dess, and like a piece of a hologram or a fractal, we contain the image of the whole.†(p. 31).

One chapter discusses the life and teachings of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486-1533), a reformer in India and contemporary of Martin Luther (1483-1546). Chaitanya was said to embody Radha and Krishna as an incarnation (avatar), and he led a revitalization movement in India that paralleled the Renaissance taking place in Europe. Bohlert compares Chaitanya to Martin Luther for offering an alternative to fundamentalism, and to Jesus for breaking down caste and gender barriers. He also describes Chaitanya’s influence on the Moslem religion of his day in India. It was refreshing to me to gain new insights into Chaitanya, adding depth and detail to the introduction that ISKCON offered during the years I was a member. This is welcome, since Chaitanya does not belong to any one organization, or any one region of India. Bohlert’s book will spread Chaitanya’s teachings to a broader audience.

Bohlert mixes the worldly and next-world experiences, when he says that we have a duty here on Earth to enjoy this life. In Bohlert’s view, salvation is more than just for ourselves, in terms of wanting go to heaven when we die. He explains why our experience here is important, and offers spiritual reasons to stand up to the challenges of today. He says salvation “includes communal salvation, which involves healing the brokenness of society and individuals. Society as a whole cannot be healthy until all are healthy and whole just as the body cannot be healthy if certain parts are diseased.†(p. 42) The solution, he says, is “We need to see ourselves as part of God-dess’ extended family, as brothers and sisters in the human family, and as part of creation. Then we can solve our problems cooperatively.†(p. 47) He explains, “The more we learn to experience God-dess and consciously live in the material world responsibly, the more we spiritually evolve.†(p. 66) Put simply, “The more spiritual we become, the more we enjoy this life fully.†(p. 86)

The gift for reading the book is to go from hearing about god and goddess, to actually experiencing god and goddess. When we first pick the book to read it, we may feel like outsiders to a fundamentalist religion with few entrance doors. However, after a thorough and thoughtful read, we embody the relationship with god and goddess. The music of the spheres lights within ourselves. As Bohlert confirms, “This is living the myth.†Fundamentalist scholars from the various Hindu groups may give Bohlert grief for unleashing the mystic experience to his readers, but Bohlert has the credibility as a scholar, through his lifetime of preparation for writing this book, to make this leap for his generation. So never fear, anybody from any background may read the book and form an eternal bond with the denizens of the spiritual world. Bohlert asks the reader to throw off convention, and simply embrace the love emanating from Radha and Krishna. If more people read this book, the world will be a better place.

— Nori Muster